INTERVIEWS

Drew Neumann powered up his synthesizers and composed scores for videos from Ari Dykier, Rory Scott, and Sean Capone in Season 3, Episode 1 of iP2BU, entitled ‘Book of Lyrics.’ For that reason, and so many others, we believe he’s the perfect subject to kick off our interview series.

Drew Neumann

Drew Neumann is a musician and the composer of numerous film and television scores whose longtime friendship with artist and animator Peter Chung dates back to their shared attendance at The California Institute for the Arts. Neumann’s work includes music and sound effects for Chung’s seminal ‘Aeon Flux’ and projects for Disney, E!, Nickelodeon, MTV, Mattel, Paramount Pictures, and Cartoon Network.

By Todd McKinney

You are suddenly stricken with an earworm; that sticky sonic pest whose catalog comprises the songs you may have once enjoyed but probably aren’t enjoying now. A mild infestation typically doesn’t prevent sleep, though, and the cure can be as simple as a quick listen of the offending tune.

California composer Drew Neumann, whose impressive body of work includes scores and sound effects for some of the most forward-leaning animated video and film work of the past four decades, was afflicted in his younger years with a more complicated earworm situation.

“When I was about sixteen, I started hearing complete symphonies in my head,” Neumann says. “They were nothing I had ever heard before.” For many musicians the delivery of an unanticipated symphonic composition might seem like a boon from the Muse.

But not for a high school kid who really just needed some sleep. “They kept me up all night,” he says. “It was annoying as hell.”

It may be hard to a draw a straight line from those past symphonic earworms to Neumann’s current output of sonic riches, but it’s easy to see that his connection to his muse has been solid for a long while.

The son of an engineer father and a mother who was a classically trained pianist (“She could really rip,” he says), Neumann sang in elementary and junior-high choir, built various Radio Shack and Heathkit projects with his father, and “… got used to the smell of solder early on. I am absolutely a product of my parents,” he says.

Wendy Carlos‘ 1968 release of ‘Switched on Bach,’ which earned her three Emmy Awards, really grabbed Neumann by the ears. “I loved it, even though it was so early in electronic music,” says Neumann. “Some parts were a little out of tune, but it was awesome for the time.”

Then, in 1971, Carlos composed the music for Stanley Kubrick’s groundbreaking ‘A Clockwork Orange;’ that score was a guiding star for Neumann’s vector of artistic creation. His reaction then to that album summed it up for a ‘70s kid: ‘Wow … this is the F-ticket to Disneyland.’ Neumann says, “I became obsessed with learning what a synthesizer was and how it worked.”

But that F-ticket required at least one decent piece of kit to get the ride rolling; Neumann had none. “I couldn’t afford a MiniMoog or an Arp Odyssey, but I knew I could flip pizzas at Little Caesar’s and save up enough to buy a Roland System 100 Keyboard,” Neumann says. He describes his early work as ’noodling to tape,’ but the noodles refined over time and Neumann became increasingly focused on the possibilities available to a young player with a small synthesizer and the fire to fuel it.

“When I was about sixteen, I started hearing complete symphonies in my head. They were nothing I had ever heard before. They kept me up all night ... It was annoying as hell."

Drew Neumann

After high school, Neumann landed at the University of Michigan. “It took me two years at U-M to realize that I wasn’t going to be a graphic designer,” he says. But the university’s inability to ignite that portion of Neumann’s creativity was, in hindsight, a gift both to the nascent composer and to millions of future fans of the animated arts.

Neumann outgrew the Roland 100 and was able to trade up to that Arp Odyssey during the summer between school years at U-M.

The Disneyland reference gains traction in relation to Walt Disney’s support for the California Institute for the Arts, a private arts college in Santa Clarita, California, Neumann’s next education locale. Mr. Disney had been an early benefactor and guiding force in the development of CalArts, and a proponent of the Wagnerian ethos of Gesamtkunstwerk (‘total art’). A central goal of the college was to encourage creation which engaged multiple art forms and media, and a cooperation of many contributors; Disney had used the same principle when developing the Walt Disney studio environment.

“I got into CalArts after proposing to the Film Graphics and Experimental Animation Department my plan to create projects using completely abstract visuals with electronic music behind them,” Neumann says. “It was very much like what we’re doing with I Promise 2 Be You.” Neumann set out to earn a degree in experimental animation and video effects with a minor in electronic music.

At CalArts he befriended fellow student Peter Chung, now renowned for his angular characters and unique animation style on Liquid Television’s ‘Æon Flux,’ and on multiple other projects to come. Neumann says, “Peter did his first hand-drawn animated student film with a moving camera technique, different perspectives, all amazing stuff, and I thought, ‘This guy is a first-year student, just out of high school?’”

Later in his career, Chung was the lead character designer for the animated series ‘Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,’ ‘C.O.P.S.,’ ‘Phantom 2040,’ and ‘Reign: The Conqueror.’ He co-designed the characters in the popular Nickelodeon series ‘Rugrats,’ and co-directed both its pilot, ‘Tommy Pickles and The Great White Thing’ and ‘Rugrats’ opening sequence.

Neumann’s technical expertise increased through access to CalArt’s 100- and 200-Series Buchla synthesizers (“a fantastic learning experience,” he says); he traded up his Arp Odyssey for a Sequential Circuits Pro One.

In a blindingly bright bit of luck, Jerry Moseley, a representative for DeltaLab, walked past an open door in CalArts studio E105 when Neumann was working on music for his own film project. Moseley liked what he heard; he and Neumann created a demo recording together to promote the DL-2 Acousticomputer, an early digital delay and reverb effects box.

Moseley later became director of Fairlight US (distributor of the groundbreaking Fairlight CMI synthesizer, sampler and digital audio workstation) and eventually arranged for a Fairlight CMI to be housed in Neumann’s dorm room for a month.

With it, Neumann learned, among other fundamental audio design lessons, a waveform–drawing approach to sound creation which has benefited his ability to recognize detailed audio components of any sound and use that knowledge to accurately recreate or enhance it.

Anyway, a $32k Fairlight CMI.

In his dorm room.

Other future animators and filmmakers developed their craft during those years at CalArts, and Neumann was tapped to score Wesley Archer’s ‘Jac Mac and Rad Boy Go!,’ Bill Kopp’s ‘Observational Hazard,’ (which garnered a Student Academy Award), and David Daniel’s maximalist strata-cut film ‘Buzz Box.’ All three of these early collaborators continued to serious success: Daniels’ later work included the animation on Peter Gabriel’s ’Big Time’ music video and segments of Pee-wee Herman’s ‘Pee-wee’s Playhouse;’ Archer directed dozens of episodes of ‘The Simpsons,’ ’Rick and Morty,’ and ‘King of the Hill,’ among others; Kopp’s resume includes credits for producer, director, writer, animator, voice director, and voice actor, variously, on seven feature films and more than two dozen television series.

In 1987, Neumann’s score for ‘Buzz Box’ got a spin on Los Angeles public radio station KCRW, and, in another click of the wheel of fate, Jim Kosub, the chief editor of Movietime, (which would later become E! Entertainment Television) heard the show and contacted Neumann for a chat. Neumann was out of work at the time, so he successfully pitched a job as a video editor there.

A job that he did.

For a while.

That is, until Neumann was invited to be a guest composer at the Centre International de Recherche Musicale in Nice, France.

For a year.

There, housed in the languid and legendary French Riviera, Neumann nurtured his composition skills and co-created, among other projects, “ … a ballet for 4 dancers and a robot” with Michel Redolfi and Michel Pascal.

Back in the states, Neumann returned to Movietime and was there for the 1989 switchover to E!. Neumann says, “My job there was a foot in the door for scoring show opens, bumpers, teasers and trailers.”

Neumann had also been busy building sound effects for ‘Roller Coaster Rabbit’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast’ for Disney, and for fellow Michigan native Sam Raimi’s ‘Evil Dead 2.’ For that film, Neumann and Bruce Campbell (who played the lead character Ash Williams in the film) spent a month in a room in Eagle Rock, California just cranking out sound effects.

In the film’s infamous ‘Sammy-Cam’scene, in which Ash is being dragged through the woods, they captured Neumann’s voice through the AKAI S612 sampler to build a long scream, and used a pitch bender to modulate the effect over an octave.

“When I first saw the Aeon Flux shorts, they were silent,” Neumann says. “I asked Peter to put me in touch with the sound effects staff so my music wouldn’t step on any toes. Peter said, ‘Oh no, you’re doing all of it.’"

Peter Chung’s ‘Aeon Flux’ started in 1990 as a series of animated visual action shorts; he reached out to Neumann to do the music. “When I first saw the shorts, they were silent,” Neumann says. “I asked Peter to put me in touch with the sound effects staff so my music wouldn’t step on any toes. Peter said, ‘Oh no, you’re doing all of it.’ So, I had to plan for composing all the music and all the sound effects,” Neumann says. “It felt strange that the episode lacked human voices, so I added those too.”

‘Aeon Flux’ premiered on MTV’s experimental animation show ‘Liquid Television’ in 1991 as a six-part serial of short films, followed in 1992 by five individual short episodes. In 1995, MTV ordered a season of ten 30-minute episodes, which aired as a stand-alone series. Neumann was managing the music composition, voices, and sound effects creation for all of it until the half hour show came along.

“When we got to the 30-minute series things changed a lot,” Neumann says. “Peter liked things very understated … no over-the-top cartoon voices, for example. So all the music had to come down around that. There wasn’t enough time in the day for me to do music and effects, so I just did music”

By that time, Chung was busy animating the series, so his hands-on daily connection to ongoing post-production was diminished. Neumann did spotting sessions (in which the music cues are planned while watching the video) with director Howard Baker, who had been assigned to oversee post-production. Russell Brower and Matt Thorne took over the sound effects chores, freeing up Neumann to concentrate on what would eventually be nearly three hours of original music, meticulously planned and cut to video.

In 1995, while launching into the half hour ‘Aeon Flux’ series, Neumann heard from musician and effects collaborator Peter Stone about a new synthesizer from Germany. “Stone was a huge PPG and Waldorf Microwave fan, and he said,“You have to hear this thing. It’s like a stack of wavetable synths.”

“It was called the Waldorf Wave,” Neumann says. “I did some research and learned there were only two of them in the U.S. One was owned by composer Hans Zimmer.”

Zimmer had already scored several feature films, including ‘Thelma and Louise,‘ ’True Romance,‘ ’Rain Man,’ and, the year before, he had finished work on ‘The Lion King,’ a score that earned an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, and two Grammys. Neumann rightly assumed that the new synth might be a groundbreaker noisemaker.

Around that time Geoff Farr, a former sales rep for Oberheim Electronics (and currently the executive producer of iP2BU), had started his own synth distribution company in Los Angeles, with the U.S. rights to carry the Waldorf Wave. Farr indeed owned the second Wave in the U.S., and Neumann was on it.

“I went down to his place in Santa Monica, waved a bunch of cash at him and said, ‘I need this thing right now,’” Neumann recalls. The enthusiastic first connection paid off for them both. “Many of the signature sounds of the ‘Aeon Flux’ universe came out of that synth,” says Neumann. “And Geoff and I have been friends ever since.”

Farr’s support of Neumann’s extensive synthesizer programming and composition has grown over the years. In 2011, he introduced Neumann to Tom Oberheim, for whom Neumann worked as a product consultant for seven years. Farr has delivered numerous synthesizer prototypes and early releases to Neumann for an in-depth shakedown. If the instrument passes muster, it’s considered as a possible inclusion in Farr’s GSF Agency product line. Currently, that stable includes the Knif Audio Knifonium, the Regen from Synclavier Digital, and the UDO Audio line of synths: the Super 6, Super 6 Desktop, and the new Super Gemini.

In April of 2023, while working on playlists for season three of iP2BU, Farr realized that some of the submissions had powerful visual animation but lacked sufficient audio tracks. Rather than asking the videographers to add new audio, he contacted Neumann and arranged brief introductions between the composer and the video artists.

Rory Scott is a Chicago-based multidisciplinary artist whose vibrant, active visuals were, in Farr’s estimation, a perfect match for what he knew Neumann would bring to the project.

“The original audio track on Rory Scott’s ‘TL23’ had an 83 beats-per-minute tempo. I started there, working with the picture, composing section by section,” Neumann says. “I fired up the Sequential Tempest Drum Machine and ran it through a 1010 Music LLC FXbox … a very cool Euro module for which I had helped develop presets. It can drastically change effects beat by beat,” Neumann says. “That became the initial framework for the score.”

Neumann adds, “I was seeing lightning flashing on the video horizon, so I added some thunder from 1010’s Nanobox Lemondrop Granular Synth.” When the score was complete it was delivered to Scott, and Neumann waited for a response. “I didn’t hear anything from her for several days,” he says. “I thought, ‘oh shit, she didn’t like it.’ When we finally heard from her, the response was off the rails … and in a good way. She even prepared a new render with ray–traced elements.” The finished work is featured in the premier episode of iP2BU Season Three.

Polish videographer Ari Dykier, who, in his own words creates ”… unique worlds of dreams, memories, and symbols,” was another of the dozen-plus artists who submitted works for iP2BU consideration. His ambitious and active ‘Windsor,’a short black-and-white piece with breakneck image changes, multiple levels of clip-art moving objects and a distinct nineteenth century flavor, stood out. Neumann’s approach on this was to blend Dykier’s original drum track with music beds from earlier impromptu creative music sessions with his friend Mark Vail, a musician and writer whose books on vintage and modern synthesizers are encyclopedic in scope. In the first episode,

Vail visits Neumann’s studio a few times a year, bringing a small battery-powered set of synths and processors, to which Neumann adds layers of sequenced, flowing, and often slowly developing electronic elements. Their various 2022-2023 in-person and internet tag team sessions yielded more than four hours of completed compositions.

Neumann surveyed those musical assets, selecting sections that were well-matched for ‘Windsor’ in feel, tempo and timbre. He added other hits and musical phrases to accentuate dynamic moments in the video, using various other synths in his stable of instruments.

The composer’s sonic arsenal continues to grow, in part because of his consultation and sound development for a long list of premier audio gear manufacturers, including 1010 Music LLC, Arturia, Studio Electronics, Ensoniq, Oberheim, Sequential, Waldorf, Moog, and most recently for UDO Audio, whose Super 6 12-voice polyphonic analog hybrid synth has earned a top spot in Neumann’s A-list of instruments.

“The Super 6 is the stereo glue on a lot of these videos,” says Neumann.

“I went back to the archives recently and listened to my work on ‘Aaahh!!! Real Monsters.’ Some cues had as many as 132 tempo changes per minute,” Neumann says. “Cranking out that kind of work required sixty-hour hour weeks. I was getting up at three in the morning and working until I couldn’t keep my eyes open.”

Sean Capone, an original contributor to iP2BU Seasons One and Two, continues to be a proactive partner in the new season of iP2BU. The Rochester, New York native has built a 30-year career creating and refining moving-image-based public art commissions and site-specific ‘video murals’ incorporating animation, projection mapping, and architectural LED screens. He asserts that, “Contemporary life inhabits the space of the screen. Whether projected or transmitted, video is no longer a surface to be viewed, but an environment to be occupied.”

For his composition on Capone’s ‘GEOMANTIC,’ Neumann created an Indonesian-flavored track featuring the Super 6 keyboard and Super 6 Desktop, the Synclavier Digital Regen, the Ensoniq TS10 (and the library Neumann created for the company), and three plug-ins: the Moog Clusterflux, the Dawesome Love, and the Relab LX480.

The Super 6s provided the wide-stereo shimmering pads; the track was enhanced by the Regen synth, which offers up notably unique sounds using legacy technology from the famed Synclavier, a ‘70s supersynth which, like the Fairlight CMI mentioned above, had a starting cost in low 5 figures and was utilized by a who’s who in the music business. Neumann used the Regen to produce a tongue drum/pot gong patch reminiscent of Javanese and Balinese gamelan music, lending to the piece a beautiful sense of serenity.

“CalArts has a gamelan room next to the experimental animation class, and when I was there we’d hear their practice sessions. The sound and tuning of those instruments has remained with me over the years,” Neumann says. “Similar timbres on the Regen … including my own Seruling flute phrases … invoked the same sort of musical ambience.”

A notable Neumann composition that will heard in upcoming episodes of iP2BU is ‘1000 Paths,’ initially composed and recorded as a tribute to friends at Moog Music in North Carolina who suffered through recent layoffs.

Because of his longstanding work with Moog, Neumann had had built friendships with many employees, so the abrupt downsizing hit close to home.

“I powered up all my Moog instruments … Animoog Z, Moog One 8- and 16-voice, Moog Voyager, Little Phatty and Sub Phatty, the Model D, and a Moog Subsequent 37 … and created 32 stereo tracks of Moogs, with a little bit of my usual processing tricks, in tribute to the company and its people,” he says. “I was moved by the effect on the lives of so many people I knew. That energy, that emotion, worked its way into the composition,” he says. “At least I hope it did.”

The ascendance of a more relaxing ethos in his music may be a natural progression for a composer whose oeuvre comprises an audio record spanning decades of evolving music creation for the visual arts. From the ‘strata-cut’ clay work of David Daniels, and Chung’s angular noir motion in ‘Aeon Flux,’ to the rich variety of vision in the iP2BU universe, Neumann’s reservoir of sonic potential remains full, even though the sensibilities of a mature artist may differ from those of an earlier version of the man.

“I went back to the archives recently and listened to my work on ‘Aaahh!!! Real Monsters.’ Some cues had as many as 132 tempo changes per minute,” Neumann says. “Cranking out that kind of work required sixty-hour hour weeks. I was getting up at three in the morning and working until I couldn’t keep my eyes open.”

Neumann pauses, then says, “These days I’m a little more into gentle, relaxing, ambient kinds of things.”

-November, 2023

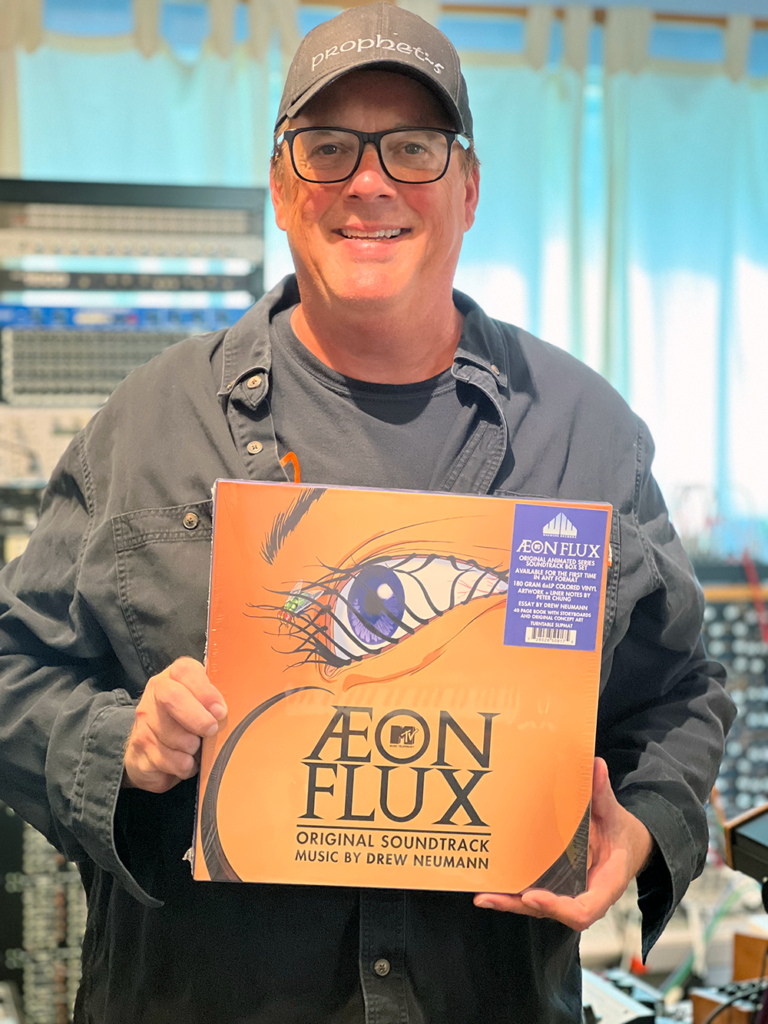

A boxed set of Neumann’s complete Aeon Flux soundtrack has been released by Waxwork Records and is available on CD and in a special 6-LP pressing on 180-gram colored vinyl. The set features remastered tracks from the original studio recordings, a deluxe, perfect-bound soft-touch book, and original artwork by Peter Chung throughout, including on a turntable slip-mat. The CD and vinyl sets are widely available online.